Hello, friends, and welcome, new subscribers! My ADHD brain is a bit scattered and prone to change things last minute, but here in The Purple Vale you can count on reflections on folklore, fairy tales, and the seasons from my little corner of East Tennessee–which is unceded Cherokee and Muskogee land.

I’ve been trying to write this post for months. Now’s the time. It feels like a bit of a ramble, so hopefully it’s coherent enough!

There are parts of us that reveal themselves only when we write. There are hidden corners that come to light with startling clarity when we put our fingers to the keyboard, or pen to paper.

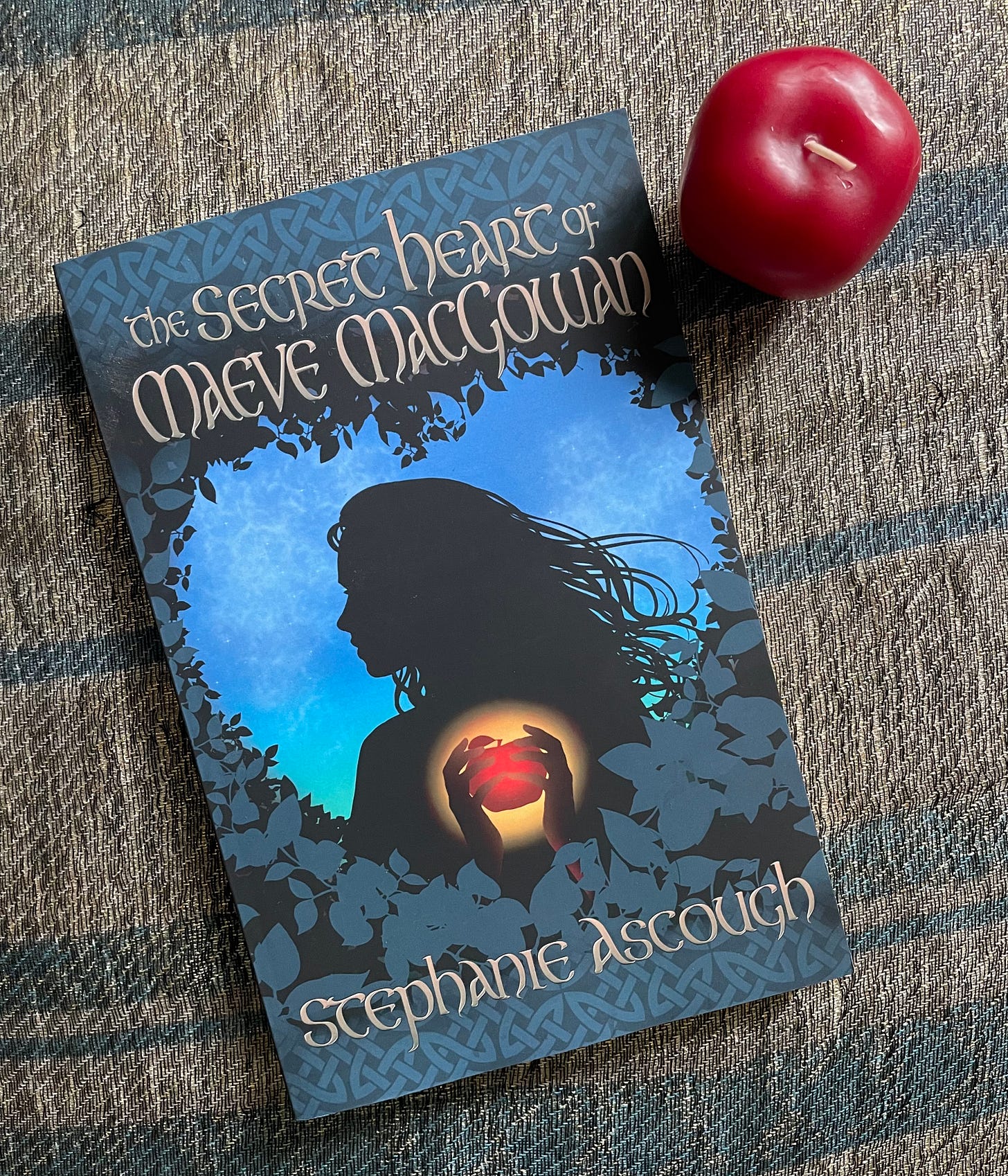

Early in the drafting stage of The Secret Heart of Maeve MacGowan, I became aware that the setting was a reflection of parts of my own subconscious.

Dr. Clarissa Pinkola-Estés, who is much quoted around here, writes about fairy tales as a reflection of one individual psyche. The princess, the hero, the villain in the story–they’re all part of the same inner landscape. They are pieces of a whole.

The dark mother (I also talk about her a lot here in the Vale) is a figure who could also be called the shadow self. In stories, she confronts the main character and draws their attention to truths long-buried or ignored.

In Maeve, the character who most thoroughly embodies the dark mother figure is someone living far beyond the fringes of Maeve’s community. This makes sense, since our shadow self is often someone with whom we don’t care to have more than a passing relationship. The dark mother shows us things about ourselves and the world we’d rather not acknowledge. Meeting her can be painful. It can be our undoing. Yet it’s never destructive for destruction’s sake. An encounter with the dark mother is a remaking, a renewing–if we let it be.

This dark mother figure in my book challenges Maeve’s perspective, especially on whether following the rules is actually as good and safe as it seems, especially for those on the margins (those people for whom the rules were never really meant to apply to in the first place).

Now I think it’s totally valid and beautiful to recognize the kinship between Maeve and those she encounters through the personal psyche lens: when we meet those parts of ourselves we’ve exiled, when we recognize and embrace them, that is a good, if difficult, true, and healing thing. I would be thrilled if readers recognized this about Maeve’s story, in fact. But there are shortcomings to that reading.

First of all, not many people read books that way and I can’t expect everyone to do so. I certainly don’t pick up a novel, read a few chapters, and go, “ah yes, the villain is the main character’s externalized Predator, let’s see who else fits which role.” I read it as a story with unique players and a plot unwinding before me. I can read it in the psyche landscape way if I want to, but usually, if I’m enjoying the book, I’m so engrossed in the story that much of my analysis saves itself for later. That’s just me.

I would argue that recognizing kinship with those the dominant culture has branded as outsiders, less-than, or other, is absolutely vital for humanity. This is also something I would love readers to take away from my story. And because of this, no one writes in a void.

I keep thinking about the scene in TSHoMM where a character from an outside and othered group tells Maeve, “you’re akin to us [redacted] folks. By heart alone, I mean, nothing else, that’s for certain.”. My hope was to write Maeve’s character with as much compassion and truth as possible: that she is a young girl caught up in oppressive systems who is harmed by them and who benefits from them. That she is, at her heart, good and worthy of love. That the cost of continuous, unequivocal submission to these systems results in the dehumanizing of herself and of those around her. That she is both an individual and interconnected with many people.

The Trail of Tears is a path of over 5000 miles, so called because of the five indigenous tribes that the American government forcibly removed from their homes. I think about these people often, especially the Cherokee, because we live minutes away from this trail, marked by signs. I frequently remember those who are no longer living here, on whose land my house rests, from whose absence I benefit (at least in some material ways). And I believe both that I am good and worthy of love because it flies the face of systems that spent years telling me I’m not, so that they could control me. These two things go hand in hand if we are to truly value humanity.

Am I thinking out loud? Oh absolutely. Rambling? Possibly. I felt it was important to highlight that Maeve is part of a colony, and I struggled with intense anxiety that maybe I shouldn’t be publishing a book that centers a colonizer’s viewpoint. And yet we find ourselves in similar positions to Maeve: instrumentalized by the very institutions who promise safety and belonging, dehumanized and striving against our complicity in dehumanizing others. Even terms like ‘dark mother’ can be charged in a racially inequitable place like the country of my birth, unless we recognize and celebrate that the dark is something good to embrace, both within and without, not something to ostracize. Ostracize parts of ourselves, and we ostracize others, too.

So I want to acknowledge two things: the beauty of the inner landscape of The Secret Heart of Maeve MacGowan, and the complicity of my imagination. The beauty of humanity, and the cruelty. The inner and outer worlds and how they show up in the pages of my writing. Sacred subconscious and ugly colonialism. The richness and glory of my imagination, and the need to continue decolonizing it.

And through it all, the dark mother keeps calling to me, in my writing, in stories, in nature, in my mind. She has many names. I believe she is there for anyone who is brave enough to meet her in the underworld. We might only have to look deep within.

Meet you over the orchard wall, friends.*

*One of my wonderful early readers for The Secret Heart of Maeve MacGowan started signing her emails like this. I like it.